Migration to NoSQL (2)

Published:

[Following my first blog post, here I am going to further discuss some ideas on my project, propose a formal specification language and introduce a concrete example taken from TPC-C benchmark]

Intro

It is a well-known fact that nowadays application developers are inclined to choose responsiveness and performance over data consistency in the CAP war. However, despite of many recent academic papers [1,2,3,4] that all try to answer the question “how to safely execute distributed applications with minimal inter-node synchronization”, there still seems to be a large gap between the process of application development over traditional strongly consistent environments and modern weaker counterparts (I’ll discuss further this claim in the next blog post, where I will explain in detail how my proposal is different than each of the above papers).

In other words, designing applications over weakly consistent data (e.g most of the NoSQL databases) is generally considered a separate skill that targets very specific use cases, for certain applications that offer different safety guarantees compared to the traditional ones. For example, when comparing twissandra with a traditional microblogging application, we see not just different data models and low-level implementation, but also new (traditionally considered incorrect) behaviors (such as temporarily visible posts of unfollowed users in your timeline) that developers have decided to live with.

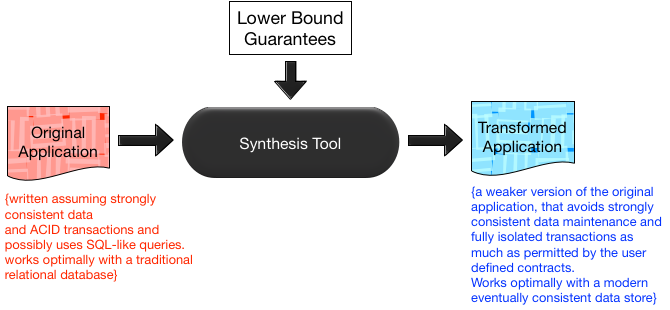

My goal is to fill this design gap by a tool that automatically analyzes an SQL-based application code and given a minimal set of correctness requirements, applies some (known) techniques (to NoSQL application developers) and synthesizes a new (hopefully faster) version of the application which guarantees the requested correctness criteria and offers better performance and availability by partially giving up the global synchronization required for unnecessary properties of the application which are not explicitly asked for.

In the following, first I am going to propose a specification language that seems to be able to capture all interesting properties of distributed systems (in fact, it might be too strong for a real synthesis tool) and then I will use the TPC-C benchmark to elaborate what kinds of application transformation I am looking into.

Specification Language

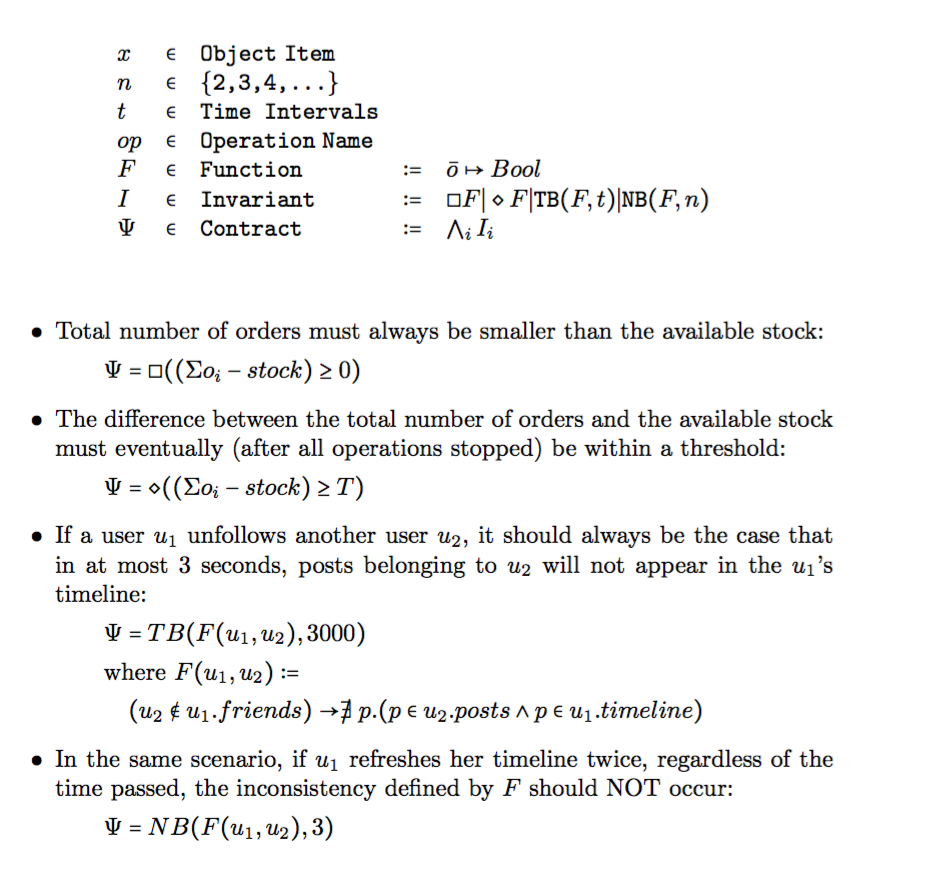

Here I will propose a language that can capture many interesting very high-level properties of distributed applications. At this point, it is not clear to me how this language can guide the design of the verified synthesis tool, however, I am willing to consider the best case scenario with a very (optimistically) strong language. The language is basically temporal logic equipped with user-defined boolean functions (the structure of these functions is yet to be discussed, but we can assume basic programming predicates over shared objects and entities). Moreover, in order to capture the time-bounded and trial-bounded invariants, I use TB(F,t) and NB(F,n) notations.

Time bounded invariants: The time bounded invariant TB(F,t) basically asks the system for a guarantee on two consecutive executions of function F that are at least t milliseconds apart, to return True the second time, assuming all other operations have stopped (in other words, it is simply eventual consistency with a limited convergence time). For example, the developer of a microblog application, might be interested in ensuring that a post from a user, will not show up in a timeline, 1 second after they have been unfollowed (although it is fine if it happens within the 1 second time limit). Note that I am not sure how useful this can be for developers; maybe a more interesting variant should remove the condition of other threads being ceased and should be able to guarantee the convergence, regardless of the other actions being performed in the system.

Trial bounded invariants: Similarly, the developers might be interested in specifying that certain inconsistencies would not occur multiple times in a row. For example, in the microblogging application mentioned above, the developer might request that after refreshing the timeline 3 times, there would not be any post by an unfollowed user.

Note that, there is no constraint on the set of objects and boolean functions that can be used in this language, which means that it is indeed able to capture any kind of high-level properties that developers can think of. Intuitively, this means that there does NOT exist a higher level language in which developers may think and then translate their requirements into a weaker language.

For example, consider an application managing an inventory and its incoming orders. A developer might be interested in weakening the guarantee of strong equivalence of the total of incoming orders and shipped items to an eventual equivalence. However, one might ask how we can be sure this would not violate correctness of the application? The answer is that, you should first define what you mean by “correctness”? All such definitions can be captured in this language themselves. For example, if you want the difference between the orders taken and the available stock to be below a certain threshold, you can indeed specify that itself in this language and there is no need to reason about the eventual equivalence of entities.

The following is the formal specification of my proposed language followed by multiple interesting examples:

TPC-C Example:

Here, I will use the TPC-C benchmark to explain how a SQL-backed application can be transformed into a NoSQL version admitting certain “disciplined” inconsistencies.

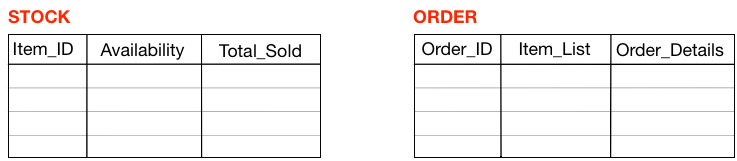

The benchmark outlines a large company with warehouses supporting multiple districts, which process orders from various customers and maintain stock levels which requires many detailed transactions with certain safety guarantees. In the following, I will introduce a simplified and slightly altered version of the benchmark consisting of only 2 of the tables and 1 transaction.

When a new order consisting of multiple items is submitted to the system, the NewOrder transaction is called which performs the following tasks:

- Place a new row in the ORDER table including the given details on the items in the order

- Retrieve data from multiple tables about the district’s sales tax and unit price for every item in the order (which we omit here)

- Retrieve some history including the discount for the customer of the order (not included in our model)

- Process each item in the order list and add a new row in the ORDER-LINE table for later processing by shipment department (not included)

- Modify the STOCK table, by updating the available stock for each item and the total of each item sold so far.

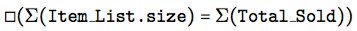

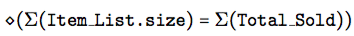

Here, we only consider two tasks: adding a new row to the ORDER table and modifying rows in the STOCK table accordingly for each item. Note that, because of the TPC-C benchmark safety requirements the above transaction must be performed inside an ACID database transaction which we can then easily verify that the total number of items in all submitted orders (recorded in the ORDER table) is always equal to the total number of items removed from the stock (recorded in the STOCK table). Formally, the following contract holds:

New let’s assume due to the massive expansions in the company, to achieve better scalability developers decide to weaken some of the strong properties of the original application. It is easy to reason that the above contract is not critical for correctness (of our simplified version) of the application and an eventual equivalence of the totals suffices. This way, the application can take the updates to the STOCK table off the critical path:

As mentioned earlier, if the application was more complex including many other entities, we should have added more contracts regarding those entities as well, to ensure that by weakening the above property, other parts of the application would still behave correctly. For example, if the pricing algorithm of the company is dependent on the available items at the time of the order processing, another contract must be written about the total profit made eventually. My tool will take all such contracts, and guarantees that they would never be violated.

NoSQL databases are optimized for these types of asynchronous concurrent data manipulations. There are in fact many techniques available that allow implementation of eventually consistent grow only counters (which is basically what the Total_Sold column is) such as CRDTs or the effect-based method of Quelea.

Such techniques make NoSQL database very attractive for any application with such weak requirements. However, applications are not usually this simple and include other parts that might require stronger and more critical guarantees. As I explained in the previous post, the transformation of SQL-backed applications to the NoSQL versions, is not a trivial (or at least, not an easy) task. If the developers decide to weaken some of the properties of the original application (which rationally they should, because otherwise there is no point in moving to NoSQL database if they are looking for the same strong properties), the complexity of different (possibly interfering) guarantees that are required by different parts of the application, makes this transition even more complex and non-trivial.

Epilogue

My goal is to offer developers a platform to write their SQL-backed applications, and then write multiple lower-bound high level guarantees (maybe a more interesting tool would actually be able to suggest different kinds of weakenings to choose from). The tool then analyzes the code and the given contracts, and returns a new (faster and more scalable) version of the application with formal proofs of the preservation of the requested guarantees.

Leave a Comment